1971-03-27

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, now faces the crisis he has always feared

By Paul Martin

Page: 12

The making of a martyr

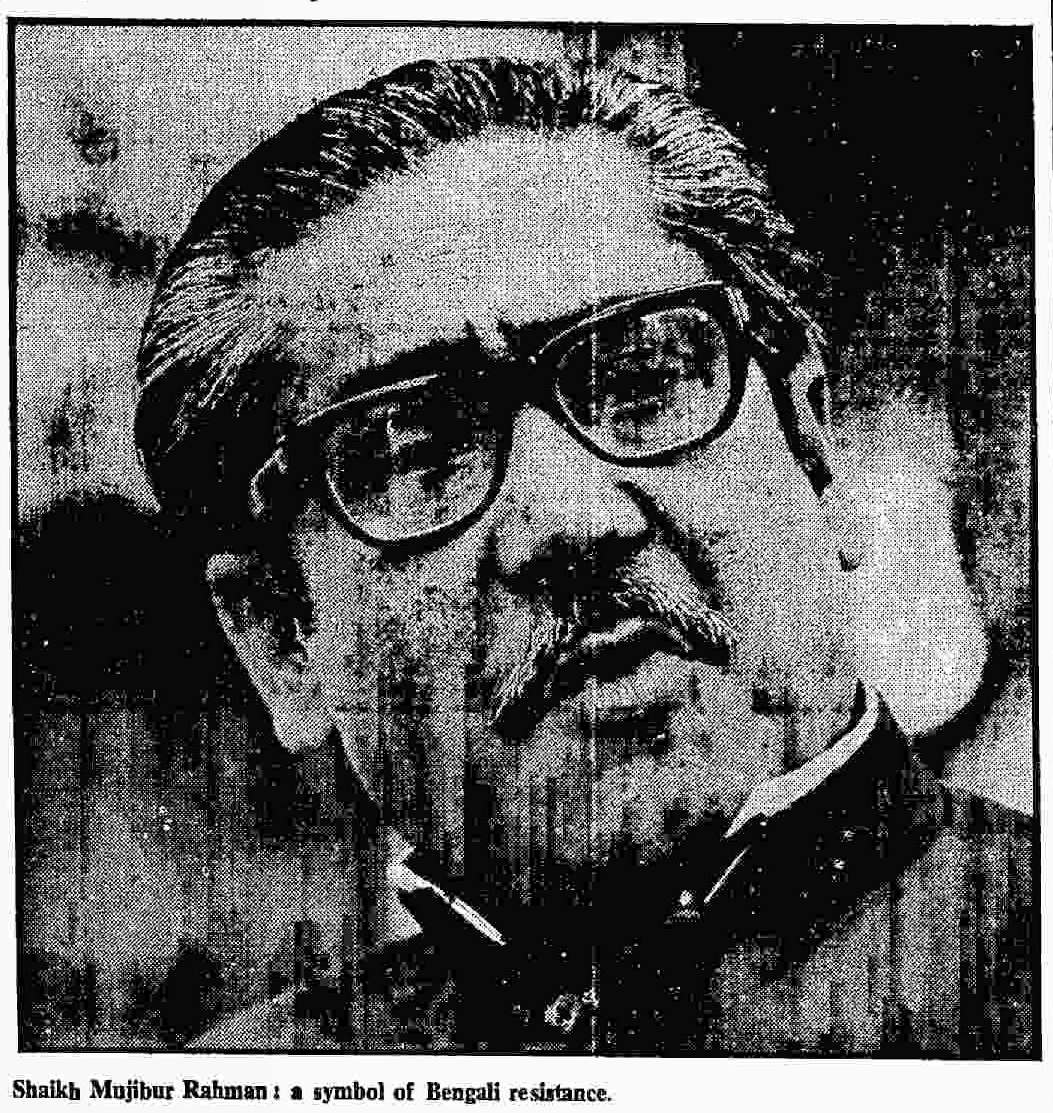

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the East Pakistan leader who has called on his people to stand united against the Pakistan military regime, is a symbol of resistance. The greater part of the past 20 years of his life have been spent as a political prisoner. Today, as he leads East Pakistan through the most critical stage of its struggle, he can count on even more support than the 96 per cent of the election vote he won in East Bengal to make him the majority leader in all of Pakistan.

“Let the army come and take me to prison,” he scoffed in a recent interview with me at his home in Dacca. “Look for yourself, I have nobody guarding me. They have all the guns. They can kill me. Indeed, they can kill my family. But let them know that they cannot kill the spirit of 76 million people. The people are believe in me and they will die for their rights. They have shown it. Guns will never silence the voice of the people of Bengal.”

The past three weeks have weighted heavily on Sheikh Mujibur. His battle has been on two fronts. The ardent hope that the Pakistan crisis could be settled within the framework of the democracy promised by the country’s general election compelled him to work tirelessly to the negotiations with President Yahya Khan. The call for Bengali independence which had infected the populace in the past month bringing province-wide civil disobedience in protest against the military regime pitted his political prestige and personal support against the challenging voice of the extremists within his own movement.

Indeed, it is ironic that the military regime’s decision to use force in an attempt to impose a settlement in favour of the west wing in the Pakistan constitutional crisis, may be the decisive blow which ends the concept of a united Pakistan. For Sheikh Mujibur, though representing the essence of Bengali nationalism, is undoubtedly a greater patriot than many leaders from West Pakistan who support the regime’s latest militant stand.

Tall and engagingly handsome Sheikh Mujibur, who is 51, looks like a successful businessman. He conducts his politics in the manner that is customary with the tribal leader in Islamic societies. His endurance, since the crisis began with the cancellation at the beginning of the month of the National Assembly, has been remarkable. Between constant sittings with the inner council of the Awami League, drafting policy and running the administrative affairs of the province, he has also played host to a stream of political leaders from West Pakistan who have joined in the efforts to find a solution to the crisis. On top of that, his house has been the rallying point for Bangladesh nationalists.

“What I want is emancipation for my people,” the Sheikh said, maintaining the policy he has hitherto taken, even in public rallies, of avoiding the mention of independence. “Let us face it - even when the British ruled India they did not tax us. They reaped the fruits of the land but they did not impose taxes on us. At the moment we are being treated by the West Pakistanis as a mere colony and a market place. We have our rights and these were underlined in the results of the elections. Only a few days after her election, Mrs. Gandhi was sworn in as Prime Minister. My election was last year but I am still waiting to be sworn in.”

After an early mission school education, Sheikh Mujibur graduated from the Calcutta Islamia College just before partition. His political life dates back to the early 1940s when he was elected to the Council of the All India Muslim Students Federation and later the Muslim League. However, after partition he broke with the Muslim League which came to power in East Bengal and under which he had his first taste of prison for his association with the first Bengali Language Movement. He was to serve four other prison sentences under successive Pakistani regimes.

The event that marked the rise of Sheikh Mujibur to a position of power and to the eventual undisputed leadership of East Pakistan, was his arrest by the regime of President Ayub Khan in 1966 under the defence of Pakistan rules. This followed soon after he first publicly stated his six-point programme for regional autonomy for East Pakistan. After spending 21 months in prison, the Sheikh was removed to military custody and became the principal defendant in the Agartala conspiracy case. It was alleged that he had plotted with members of the armed forces to get East Pakistan’s independence.

Strikes and popular demonstrations followed the Sheikh’s arrest and continued throughout the trial which lasted a year. He became the focal point for Bengali nationalism. There is no doubt that the trial itself, which ended inconclusively with the Sheikh’s release and the political unrest it created in the country, was a contributory factor in the downfall of the Ayub regime and its succession by General Yahya Khan and his military regime.

To those who have watched the Sheikh closely during the past three weeks it has been obvious that he was not unaware of his formative political years and the hardships they imposed upon him. Indeed, there were those who have long been close to him, who felt that his constant reference to his prison years and the possibility of his death, betrayed an inner wish that he would not have to face what he had always feared. As he himself put it many times: “I am an optimist. I hope for the best, but I always prepare for the worst.”